This column is guest-authored by Karen Parolek, President of Opticos Design, an architecture and urban design firm specializing in healthy, walkable, rollable and equitable communities.

When someone starts talking about building housing in your neighborhood, particularly affordable housing, or greater “density,” what’s the first image you think of? Many people immediately think of 4-story or taller, block-size apartment buildings, and some even imagine high-rises. These default images of new housing can create an immediate, often negative reaction, which is likely detrimental to the cause of building much-needed housing.

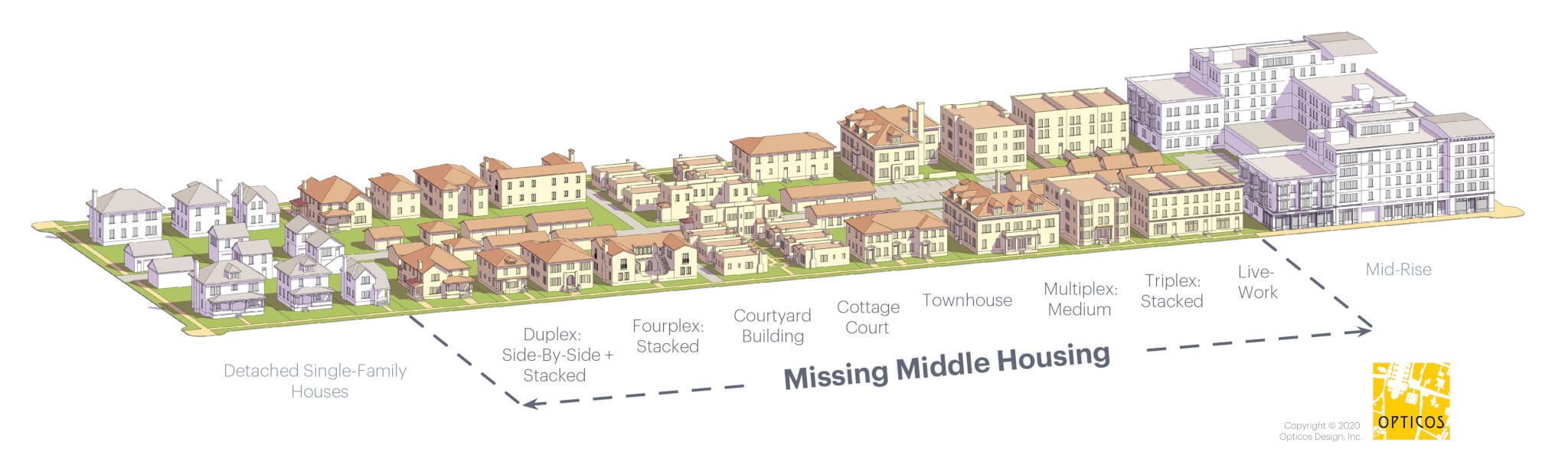

But looking across the U.S., from small towns to big cities, we see historic examples of small neighborhood-scale housing that are both beloved by the community and that have been critical historically to providing enough housing and at affordable prices. Each one looks and feels like a detached single-family house, but it includes homes for more than one family. These building types, such as duplexes, fourplexes, and small bungalow courts have been an important part of our nation’s success, but they’ve been illegal to build in most places for the past 75-100 years. At Opticos Design, we promote these building types as “Missing Middle Housing,” and they’re having a much-needed renaissance.

Missing Middle Housing (MMH) is a house-scale building with multiple units in a walkable neighborhood. It fits in so well to treasured low-rise neighborhoods that when you walk by one, you’ll likely assume it’s a single-family house. Even professional planners often need to look closely to count the mailboxes or utility meters to realize there’s more than one home inside.

MMH provides many benefits to communities. It enables communities to provide more homes in its low-rise neighborhoods that fit right in without changing the physical look and feel of the neighborhoods. This not only helps communities contribute much-needed housing, but also gives more people the opportunity to live in desirable, often high-resource neighborhoods in good locations. And providing more housing within the neighborhood also helps support better amenities for everyone, like small, local businesses, and sometimes transit services.

MMH is also more affordable than typical detached single-family houses, because the homes are smaller, so people are paying for less space, and the land cost is shared by multiple homes, so each household is paying lower land costs. It also has less parking, lowering the land costs even further. This makes MMH an excellent way to contribute market-rate middle-income housing to the community.1

Historically, MMH often provided the first opportunity for families to purchase or build their housing by pooling family money to house multiple relations in one building, or by providing rental income from the extra homes. In her book Becoming, Michelle Obama describes growing up in a duplex that was owned by her great aunt who lived in the ground-floor unit, while she and her parents and brother lived in the upstairs apartment. Later, when her great aunt passed, her parents moved downstairs and Michelle and Barack Obama lived upstairs as newlyweds.

MMH also helps communities be more environmentally sustainable. As mentioned earlier, it uses less land per home than single-family houses, preventing sprawling development, helping protect our farmland and open spaces, and shortening commute distances. It also provides more homes in walkable neighborhoods, giving more people sustainable transportation choices, like walking, riding bikes, and taking transit.

Finally, MMH provides essential housing choices to meet a variety of needs for a variety of households. These smaller homes are in demand by many smaller households, from retirees and empty-nesters looking to downsize but stay in the neighborhood, to young adults, who are often waiting longer to start a family and don’t yet need a large house; from single professionals who only require or want to pay for a small space, to single-parents and small families that are looking to live closer to school and work and are willing to live in a smaller unit for that convenience and walkable-neighborhood lifestyle. They are also excellent options for multi-generational households, where each can have their own home but all in the same building, like Michelle Obama’s family.

These building types provide housing choices for people looking for less to maintain, from a smaller house to a smaller yard, where the small group of residents can gather in community while also sharing maintenance. This type of community living is desired by and beneficial to people who want or need to live within a micro-community, which appeals to many across the age and cultural spectrum. And MMH, like most housing, can be either for sale or for rent, offering even more options within the community.

As Leah Rothstein and Richard Rothstein call for in Just Action, these benefits increase the potential to bring diversity to high-resource, high-demand neighborhoods, including people of diverse ages, incomes, races, ethnicities, and household types and sizes. MMH provides diverse housing choices that allow people who may not want or be able to afford a single-family house to live in beautiful, low-rise neighborhoods with wonderful amenities and resources.

So why is it missing? One reason: the invention of single-family zoning. As Richard Rothstein describes in The Color of Law, single-family zoning was often adopted to segregate communities, creating new, white-only enclaves. When this zoning went into effect, it not only prohibited Black people and many others from living there, it also prohibited duplexes, triplexes and all other MMH that had been popular and prevalent in existing neighborhoods. It was so prevalent that you can find MMH in virtually every neighborhood that was built before the proliferation of single-family zoning in the early twentieth century. Most of our now-beloved, historic neighborhoods are full of MMH. Yet, today, over 75 percent of residentially-zoned land in the United States only allows single-family housing. In other words, MMH is illegal in most of our towns and cities.

For that reason, while examples of historic MMH exist in most pre-1930s neighborhoods, examples of newly built MMH are harder to come by. Thankfully, though, that’s changing, as communities and developers are looking for creative ways to provide more homes and at more affordable prices. Here’s one example:

In Omaha, Nebraska, Gerald Reimer spent years renovating historic MMH and was convinced there was a market to build it new. Recognizing the lack of economic integration in neighborhoods in Omaha, he was also interested in creating a neighborhood for people across a broad income spectrum, providing much needed housing choices and creating a place of social bridges, where “good things can come from serendipity and meeting people.” Mr. Reimer wanted to see if he could do “missing middle on scale… to create a model that other developers who might otherwise be cynical could come and look at it and say, ‘holy mackerel, this will work!’” He also set out to disprove the theory that economically wealthy people are not willing to live in an economically diverse neighborhood.

My firm worked with Mr. Reimer and his team to design a new neighborhood filled with mostly MMH, in nearby Papillion, Nebraska. The new units are for rent, providing residential options for people with diverse incomes, with an intentional and broad difference between the lowest and highest priced homes, currently in a range of $1,295 to $3,195 per month. To provide plenty of choices, there are homes at every $100 step within that range. That price diversity led one new resident to comment on how lucky she felt because she had never been able to afford a home in a neighborhood that she wasn’t hoping to leave. And disproving the theory that wealthy people are not interested in living in areas with economic diversity, the most expensive home was the first to rent!

Creating places with a variety of housing choices in the interest of economic diversity is one way to start to address the challenges of racial segregation. However, building MMH is just one piece of the puzzle. Additional efforts will likely be needed to ensure that these places are also racially diverse, such as specific marketing efforts to reach out to communities of color and ensuring that local banks are lending fairly and that local appraisals are not discriminatory.

As called for in Just Action, building more homes in high-resource, single-family-zoned neighborhoods is critical to helping repair the damage done by past planning practices. Missing Middle Housing can help, by blending in with the neighborhood and providing not only more homes in these neighborhoods, but also more housing choices for people with a variety of income levels and housing needs.

At Opticos, we differentiate Missing Middle Housing and middle-income housing. Middle-income housing can come in many shapes and sizes, including mid-rises. These mid-rises may or may not be appropriate to build, depending on the location, and can often generate opposition, appropriate or not. On the other hand, Missing Middle Housing is specifically housing that matches the form and scale of single-family houses in low-rise neighborhoods. This differentiation is important because the concept of Missing Middle Housing is about opening people’s hearts and minds to ways they can provide homes for more people in their wonderful neighborhoods while retaining beloved physical characteristics. So, while Missing Middle Housing can help provide middle-income housing, not all middle-income housing is Missing Middle Housing. However, in Just Action, Richard Rothstein and Leah Rothstein write “missing middle housing” to refer not to an architectural type, as we do at Opticos, but rather to housing that is affordable to households that earn too much for federal housing subsidies, but too little for market rate housing.