Residential segregation is an educational crisis

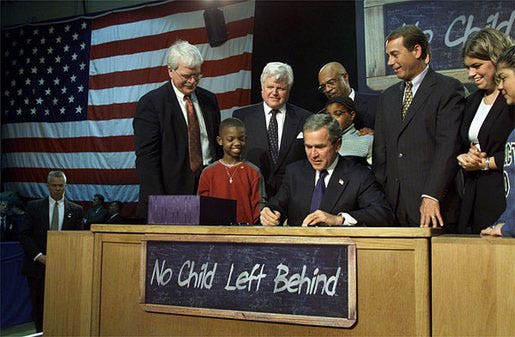

How the No Child Left Behind Act led to the Color of Law

I was recently asked how I came to write The Color of Law. The answer is this: In the 1990s and early 2000s, I had been a journalist and policy analyst studying public education. At the time, it was conventional wisdom that the “achievement gap”—black students having lower average performance than white students—was caused by lazy or incompetent teachers of low-income children. In 2002, this view, shared across the political spectrum, was enshrined in federal legislation: the “No Child Left Behind” law. Its theory was that if we shamed teachers by publishing their low-income African American students’ test scores, the teachers would work harder and the achievement gap would disappear. Residues of this law continue to this day. If you wonder why elementary and secondary schools are so obsessed with administering standardized tests and reporting their scores, it’s because of that policy.

My visits to schools that served disadvantaged pupils, where I observed so many dedicated, hard-working teachers, led me to wonder if this theory had any basis in reality. Of course there were incompetent teachers, there are substandard performers in any profession. But I concluded that lower average achievement of these pupils was primarily due to social and economic challenges that children brought with them to school—for example, greater rates of lead poisoning that resulted in damaged cognitive function; living in more polluted neighborhoods that led to a higher incidence of asthma that kept children up at night wheezing and coming to school drowsier the next day; lack of adequate health care, including dental care, that brought more children to school with distracting toothaches, and on and on.

Working at The Economic Policy Institute, I published a 2004 book, Class and Schools; it attributed the “achievement gap” not to incompetent teachers but to such social and economic disadvantages. Not every child in a predominantly low-income school had one or more of these challenges, but enough did to affect a school’s student performance.

Looking back on this now, it’s remarkable that the book treated these all as individual student disadvantages, and made very little mention of segregation. But I soon thereafter realized that it was one thing if individual students came to school with one or more of such challenges; it was quite another if many students in a school did so, overwhelming the ability of even the best teachers to overcome them. We call such schools “segregated” schools and so I began to think of school segregation as the greatest problem facing American public education. And as I thought about it further, an obvious fact struck me: the reason we have segregated schools is because they are located in segregated neighborhoods. For me, a logical next step was to view neighborhood segregation as a school problem, one that writers about education policy should consider more carefully.

This is what I was pondering when, in 2007, the Supreme Court prohibited the Louisville, Kentucky, and Seattle, Washington, districts from taking steps to desegregate their schools. The Court’s reasoning was that, true, the schools in those places were segregated because their neighborhoods were segregated, but the neighborhoods were segregated by accident—because of private discrimination, income differences, or blacks and whites choosing to live with others of the same race. Government, the Court said, was not involved in segregation and therefore was prohibited from taking explicit steps to remedy it.

Thinking about this decision provoked me to recall an incident in Louisville some years before. In 1954, a white suburbanite sold a home to a black friend, white neighbors rioted, and the white resident was arrested, tried, convicted and jailed with a 15-year sentence, for having provoked the riot by selling property in a white neighborhood to an African American. I thought, Louisville’s segregation might not be accidental (“de facto”) as Chief Justice John Roberts claimed, but rather the result of racially explicit and unconstitutional action by government (in this case, the criminal justice system, including police, prosecutors, and courts) to impose racial separation. I thought I should look into it further to see if this was an isolated incident or part of a pattern of unconstitutional government action to create the segregated residential landscape, and thus the segregated schools, with which we live today. The Color of Law, published 10 years later, resulted from this inquiry.

Last year, I discussed this inseparability of neighborhood segregation and school achievement, in an interview conducted by the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank. You can read or listen to it here.

I've been aggregating links to articles and books like this for more than a decade. So far I've not seen any consistent strategy that would change public will and reduce segregation and associated problems in high poverty areas of cities like Chicago.

That Dionissi Aliprantis conversation on ‘Public policy and the formation of residentially segregated cities’ sounds like Ta-Nehisi Coates talks to Richard Rothstein!