Should Princeton University Have Cancelled Woodrow Wilson?

David Frum is a former conservative Republican (George W. Bush’s speechwriter) and now a “Never-Trumper” who acknowledges voting for Hillary Clinton in 2016. He is currently an editor at The Atlantic where he recently published an article, “Uncancel Woodrow Wilson,” defending the record of the early twentieth century (1913-21) president.1 Frum takes particular aim at the re-naming of a Princeton University graduate school, now the School of International and Public Affairs but formerly the Woodrow Wilson School.

Before becoming governor of New Jersey and then winning the White House, Wilson had been the university’s president. The “cancellation” of his name resulted from renewed attention to Wilson’s enthusiastic support for the segregation and subordination of African Americans. Student protesters demanded the re-naming and after considerable waffling, the university agreed.

But Frum’s article goes too far. We can agree with Frum that removing Wilson’s name was ill-considered, as I was distressed when my grandchildren’s public school changed its name from Thomas Jefferson to Ruth Acty, honoring its first African American teacher.2 But in his haste to denounce “cancellation culture,” Mr. Frum minimizes how responsible Woodrow Wilson was for the segregation and racial inequality that we endure today.

Removing the names of figures like Woodrow Wilson and Thomas Jefferson signifies virtue on the part of proponents but accomplishes nothing to narrow racial inequality. It may, however, enrage those for whom reverence for Jefferson and Wilson is part of their identity as Americans, and make it less likely that they will support actual remedies for our history of racial injustice. At least some of the appeal of the “Make America Great Again” movement may be spurred by such re-namings. This could help to explain why David Frum is so opposed to Princeton’s action. We should not make it more difficult for him to lure other Republicans to join his Never-Trumper efforts.

Wilson’s legacy, while complex, caused lasting pain for generations of African American government workers and their families. Prior to the Wilson administration, the previous three Republican presidents—William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft—oversaw very slow, although inconsistent and imperfect advances in racial equality. Their most notable contribution was the creation of an integrated federal civil service that provided a substantial number of middle-class jobs to black workers in Washington, D.C. for the first time. By Wilson’s inauguration in 1913, roughly 25,000 African Americans were employed by the government, in offices and on railway mail cars. They were about five percent of the federal workforce.

Wilson reversed this progress. He authorized government departments to curtain off black workers so they could no longer work alongside whites. Lunchrooms, water fountains, and toilets in federal offices were for the first time segregated, some designated for black workers and others for whites. With the President’s approval, African American employees were prohibited from supervising whites; black workers who had risen to management positions during previous administrations were dismissed or demoted to menial jobs. The Administration implemented a new rule requiring photographs to be attached to all federal job applications, enabling agencies to more easily reject African American candidates. Today, fair employment rules consider this practice to be possible evidence of racial discrimination.3

The destruction of a significant part of the capital’s black middle class had devastating consequences for black advancement and for the victims’ and their subsequent generations’ ability to accumulate wealth. Supporting Princeton student protests in 2015, an African American lawyer wrote in The New York Times about John Davis, his grandfather who, at Wilson’s inauguration, supervised a Government Printing Office department that included many white subordinates. With his substantial federal salary, Mr. Davis owned and commuted from a farm in nearby Virginia where he and his family resided. But under Wilson, he was demoted to the job of messenger at half his previous salary and his farm was auctioned off.4

Mr. Frum wonders why we pick on Wilson rather than his successors, Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, who maintained the policies of segregation that Wilson adopted. Continuing a by-then eight-year entrenched policy of rigid segregation was a far more likely course than reversing it. We don’t, for example, excuse President Trump’s 2017 tax cuts for the wealthy by claiming that President Biden is equally responsible because he was stuck with them. Harding and Coolidge were no crusaders for racial justice, but Republicans then were content to permit very slow advances for black citizens. That’s why, in the 1932 election more African American voters retained their allegiance to the party of Lincoln by supporting the Republican incumbent Herbert Hoover than the challenger Franklin Roosevelt, a Democrat like Wilson.

David Frum also minimizes Wilson’s race policies by resuscitating the tired claim that the President was merely reflecting bigotries that were “common among people of his place, time, and rank.” If it were the case that he merely reflected unanimous opinion, we can leave to moral philosophers a debate about his responsibility. But, in truth, among people of his time, place, and rank there were vociferous opponents of his administration’s imposition of racial segregation in the government. Wilson was aware of them and made a choice for which he can and should be held responsible. As The Color of Law recounted,

In 1914, as Woodrow Wilson was segregating federal offices, the National Council of Congregational Churches adopted a resolution condemning his policy. Howard Bridgman, editor of The Congregationalist and the Christian World wrote to Wilson that his actions violated Christian principles; the editor told his readers that protesting the administration’s segregation of the civil service was the “Christian white man’s duty.” Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette’s magazine (now known as The Progressive) published a series of articles protesting Wilson’s racial policy.

And, of course, African Americans objected. Their opinions also count when we evaluate David Frum’s claim of consensus. In 1914, a delegation of black leaders met with Wilson to protest. The President justified his policy by claiming it was designed to prevent friction between black and white government workers. Afterwards, The New York Times quoted the group’s spokesman as observing: “For fifty years negro and white employees have worked together in the Government departments in Washington. It was not until the present administration came in that segregation was drastically introduced and only because of the racial prejudices of [cabinet officers].”5

While acknowledging Woodrow Wilson’s policies of segregation, David Frum claims they were outweighed by the administration’s positive accomplishments. He properly emphasizes that Wilson and his Democratic congressional majorities reversed decades of conservative economic policies that exacerbated inequality. The Wilson administration saw a reduction of tariffs that were raising the cost of living for the working class. It implemented an income tax on the wealthy. It established a central bank (the Federal Reserve) that undermined the gold standard and its bias in favor of lenders over borrowers. It enacted an eight-hour workday and overtime premium pay for railroad labor, the first such national legislation, creating a precedent for expansion of the principle. It strengthened anti-trust laws and enforcement. Wilson supported the right to vote for women and opposed literacy tests for immigrants. In the face of antisemitic opposition by the Republican Party, he appointed to the Supreme Court Louis Brandeis, a Jew who had been the most prominent and effective advocate for wage and hours legislation and who mentored a generation of future judges and justices who eventually ended the Court’s obstruction of laws to impose minimum labor standards.

Not mentioned by David Frum, but also worth remembering is Wilson’s opposition to heavy reparations by Germany after World War I. Although many of his post-war foreign policies were foolish and damaging, had his views on reparations been heeded, the collapse of the German economy during the 1920s might have been avoided or at least minimized, Adolf Hitler perhaps then would not have been able to exploit such a collapse and make Jews its scapegoats, and World War II and the Holocaust might have been avoided.

Franklin Roosevelt claimed that the progressive economic policies of his New Deal were inspired by Woodrow Wilson. David Frum notes that Harry Truman called Wilson “the greatest of the greats.”

In short, Woodrow Wilson’s legacy is complex.

So is Thomas Jefferson’s. Abraham Lincoln was inspired to oppose and then end slavery by Jefferson’s insistence, in the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal. Abolitionists generally were also motivated by those words. Jefferson himself, along with other slaveholders like George Washington, knew that their continued ownership of human beings, in conflict with their principles, was cowardly and hypocritical.

Unlike Jefferson, Washington, and Wilson, not every name associated with slavery or Jim Crow reflects sufficient complexity to justify respect. We should celebrate, for example, the decision of another Ivy League university, Yale, to re-name its residential Calhoun College. Identifying with John C. Calhoun, architect of the Confederacy’s secessionist principles, or the traitor Robert E. Lee, its military commander, betrays fundamental principles of our democracy.6 But reverence for Jefferson, Washington, or Wilson is different; it should be qualified but not banished.

We wrote Just Action to provide advocates for racial remedy with many policy and program ideas they can pursue in their own communities that would truly succeed in narrowing inequality. Re-naming campaigns was not one of them.

In Just Action, we urge that property deed clauses that prohibit ownership or occupancy by African Americans should not be removed; rather, a statement recognizing the community’s past sins, and repudiating them, should be attached to such documents. This could help to educate owners, present and subsequent, about their community’s shameful history, rather than obscure it. A similar reasoning should be applied to many building names. Public schools that retain “Jefferson” in their identities should teach that he both owned slaves and inspired the abolition of slavery. It is a contradiction about which pupils should be reminded when they see their school’s name. Indeed, all students, and their elders, are capable of comprehending such nuance.

Princeton University could have responded to student protests and recognized Wilson’s complexity without re-naming its school. It could, for example, have retained “Woodrow Wilson” in the title while requiring students to take an orientation class that reviews segregation’s history and Wilson’s powerful role in creating and reinforcing it. The policy school could have placed a paragraph atop its website describing qualifications to be kept in mind when honoring the otherwise progressive president. Now that the name has been removed, its home page should note that it was formerly the “Woodrow Wilson School” and direct students to a brief discussion of the controversy that led to the change.

David Frum’s article advocates no approaches like this, content as it is to regret the school’s reaction to Wilson’s racial legacy. Yet using that legacy as an opportunity to learn about it would neither ask too much nor too little. Removing the name obscured that opportunity. There were alternatives to “cancellation.”

David Frum, 2024. “Uncancel Woodrow Wilson.” The Atlantic, February 2.

Although Ms. Acty was fully qualified to teach any grade level, the Berkeley, California school district would initially only hire her to teach kindergarten because attendance prior to first grade was voluntary, so parents could legally refuse to enroll their children to avoid having a black teacher. Supriya Yelimeli. 2020. “Jefferson Elementary School could be renamed after the first Black teacher at Berkeley Unified; Appendix A, Ruth Acty, Brief Biography.” Berkeleyside.org, December 7.

Kathleen L. Wolgemuth, 1959. “Woodrow Wilson and Federal Segregation.” The Journal of Negro History 44 (2), April: 158-173. U.S. Employment Opportunity Commission. On-line. “Prohibited Employment Policies/Practices.” [I]nquiries [about an applicant’s race] may be used as evidence of an employer's intent to discriminate unless the questions asked can be justified by some business purpose… [Thus,] employers should not ask for a photograph of an applicant. If needed for identification purposes, a photograph may be obtained after an offer of employment is made and accepted.

Gordon J. Davis, 2015. “Wilson, Princeton, and Race.” The New York Times, November 24.

New York Times. 1914. “President Resents Negro's Criticism; Refuses to be Cross-Questioned About Racial Segregation in Government Offices. Stands by his Policy.” November 13.

Although Washington and Lee University has rejected faculty and student demands that Lee be removed from the school’s name (He served as its president after the Civil War), many elementary and secondary schools throughout the south have done so. Corey Mitchell. 2020. Data: The Schools Named After Confederate Figures. Education Week, June 17, updated February 20, 2024.

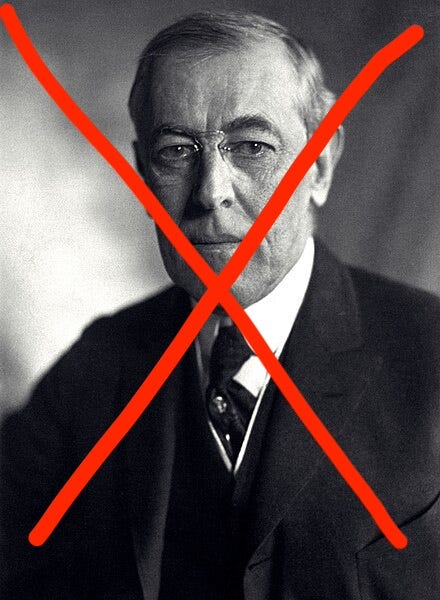

*Photo credit for unadulterated version: The Library of CongressThanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

I strongly disagree. Your article is informative, but Wilson was one of the worst presidents of all time and his name should be stricken from every public edifice. He pioneered the modern shredding of the constitution we see today. For example, Wilson pushed through unprecedented media and speech control. His administration prosecuted thousands of individuals for any government or war critique. He also pioneered mass government propaganda (ie lies) while suppressing the publics publications. Wilson implemented the undemocratic Federal Reserve while also enacted a ruinous income tax, which resulted in widening wealth gaps and cycles of recessions and misery. He ignored pleas from Black women to do something about the mass lynchings of Black men returning from Europe. He set up the League of Nations but did not support it because he did not want to submit to it. It can be argued this strategy was a light that started WWII. I could go on but Wilson was an unmitigated disaster of biblical proportions we still live with. Indeed, Wilson was the founder of Shock Doctrine theory. No to Wilson.