The Supreme Court's Consistent Lawlessness

For over a century the Court has acted to prevent racial equality; its latest affirmative action ruling is no different.

The Supreme Court’s decision to prohibit colleges from affirmative action—banning them from taking explicit steps to ensure admission of a fair share of black students—was widely expected. Indeed, it had been inevitable since Chief Justice John Roberts proclaimed in 2007 that we were a post-racial society. Fulfilling his glib but nonsensical phrase then ("The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race") and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s 2003 arbitrary assertion that affirmative action was o.k. for the time being but the Constitution would require its end no later than 2028, Republican appointees to the Supreme Court carried out what they and their predecessors had promised.

But we shouldn’t over-emphasize the current court majority’s role. In our book, Just Action, we surveyed 165 years of Supreme Court history and conclude that, with few exceptions, the Court has been on a mission to keep black citizens in a subordinate status. Had the Court not annihilated the plain meaning and intent of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, we would have a racially egalitarian society today. Discussions of reparations and remedies would be superfluous.

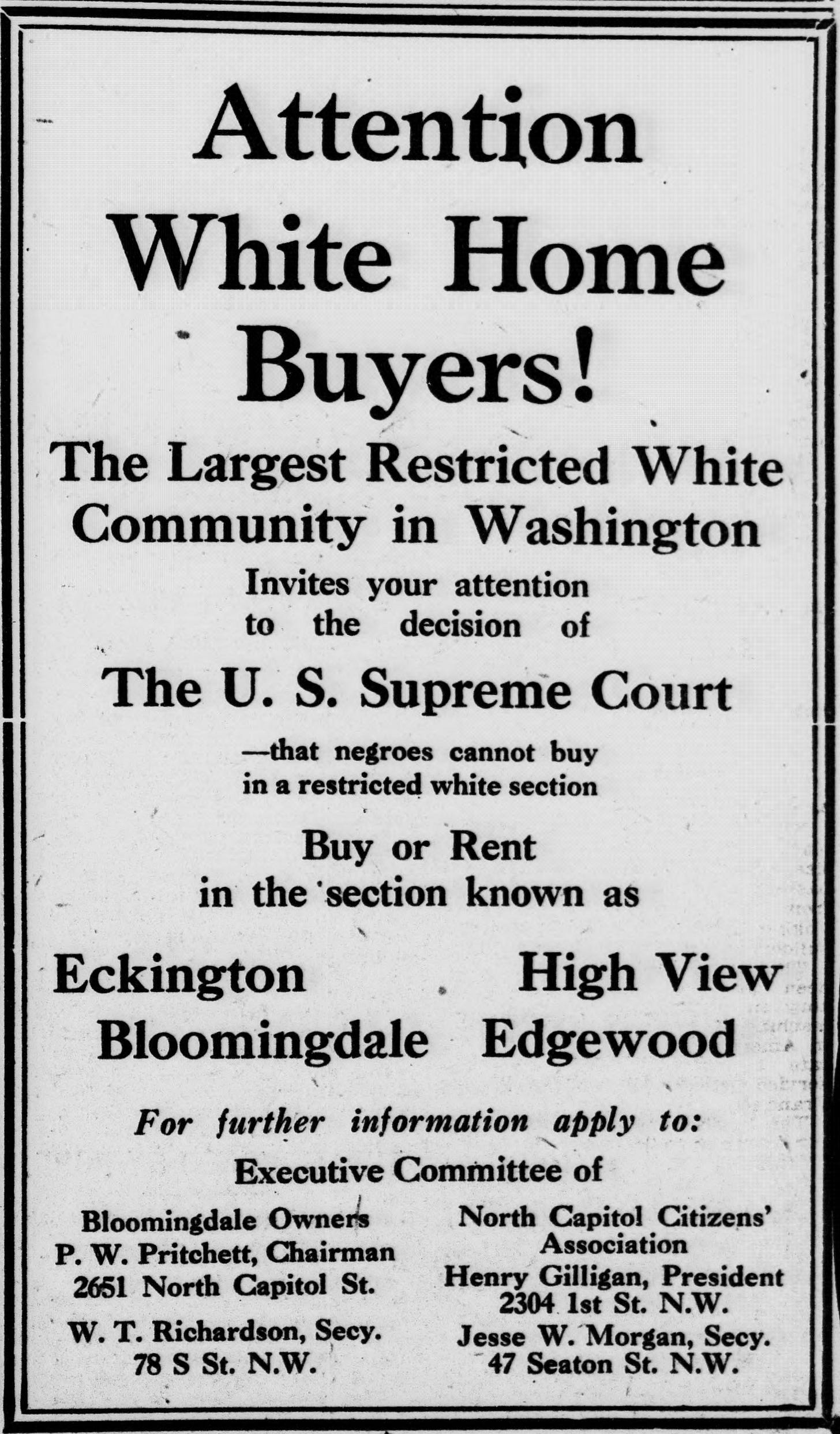

We won’t recount too many details of that history here but the newspaper advertisement above provides a particularly stark illustration.1 In the early twentieth century, developers, realtors, and neighborhood associations promoted property deed clauses (called “restrictive covenants”) that prohibited the sale, rental, or occupancy of homes by black households in white neighborhoods. In 1926 the Supreme Court blessed this practice, asserting it was purely private activity and authorizing lower courts to evict African Americans who had legitimately purchased property in areas covered by these deed clauses. Less than a week after the Court ruled, neighborhood associations boasted of the Supreme Court’s endorsement of their whites-only restriction, as in the Evening Star ad.

With promotion like this, the Supreme Court ruling became not merely an endorsement of segregation but a tool to intensify it.

Twenty-two years later, in 1948, the Supreme Court issued another ruling on racially exclusive deeds. It said (these are not the Court’s exact words), “whoops, we were wrong back then, the 1926 ruling was unconstitutional and courts have no right to evict black homeowners who purchase property with such deeds.” By that time, segregation in D.C. was firmly established and the Court offered no remedy for the black families and their descendants who had been unconstitutionally excluded from housing.

In 1866, Congress passed a civil rights act that read, in part, “citizens of every race and color… shall have the same right…to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property.”

In 1883, the Court said that Congress had exceeded its authority by banning private discrimination. Eighty-five years later, in 1968, after racial inequality had become rigid in all realms of American life, the Supreme Court said (these are not its exact words), “whoops, we were wrong back then, the 1866 civil rights law was constitutional after all,” but the Court made no effort to consider how to redress the intervening century of black citizens’ inability to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and the consequences of that inability.

In the last week, many supporters of affirmative action have bemoaned the Supreme Court’s ban of affirmative action while searching for alternative means of achieving diversity in college admissions. Typically, such advocates offer assurances that their proposed alternatives would be race-blind because they “respect the rule of law.”

We offer this brief recital to remind these proponents that the lawless party is and has been the Supreme Court, not courageous college presidents who may continue to implement race-conscious affirmative action programs. Universities should enact these programs to contribute to the remedy of a century of African American subordination imposed by a Supreme Court whose respect for the rule of law was non-existent.

If readers of this post know of other examples of private parties that used Supreme Court endorsement of racial segregation to legitimize African American exclusion, please let us know by commenting on this article.

The advertisement was reproduced in a 2019 report that recently came to our attention. The report describes in detail how Washington D.C. came to be so segregated, and the important role that restrictive covenants played to exclude African American households from the capital’s white neighborhoods, resulting in court-ordered evictions of black homebuyers. Shoenfeld, Sarah, and Mara Cherkasky. 2019. “The Rise and Demise of Racially Restrictive Covenants in Bloomingdale.” D.C. Policy Center, April 3.

Richard, Please know that in Washington State earlier this year, we enacted House Bill 1474, creating the Covenant Homeownership Account program, which will directly provide a remedy to housing discrimination. It includes an ongoing revenue source of $100 million per year on average, to pay for down payment assistance and closing costs for homeownership for folks harmed by the restrictive covenants. I would greatly appreciate an opportunity to talk with you (maybe a zoom meeting?) to discuss this advance. --- Frank Chopp, Speaker Emeritus, Washington State House of Representatives. My email is frankchopp@comcast.net. My cell is 206-612-7071. Thank you for your consideration.

We need to get real about the Supreme Court. SCOTUS is functioning the way it was designed to operate and that is to uphold white supremacy. As a political institution, historically comprised of white people, suppressing black advancement is part of its longstanding unwritten charter. Ask Justice Thomas, the sole black man on the bench, if anyone has doubts.

White supremacy ideology is deeply rooted in the American fabric. SCOTUS is just one part of its many moving parts.